La fame ci sfida. Le responsabilità europee, americane e cinesi

La fame ci sfida. Entro metà del secolo dovremo sfamare nove miliardi di persone, raddoppiando la produzione alimentare. Le responsabilità europee, americane e cinesi. La caccia ai terreni agricoli: una partita geopolitica. Vincoli finanziari e ricadute ambientali.

La fame ci sfida. Entro metà del secolo dovremo sfamare nove miliardi di persone, raddoppiando la produzione alimentare. Le responsabilità europee, americane e cinesi. La caccia ai terreni agricoli: una partita geopolitica. Vincoli finanziari e ricadute ambientali.

L’intervento di Romano Prodi pubblicato su Limes numero 4/2010 in edicola dal 30 settembre è tratto dal suo discorso tenuto al simposio internazionale “Sicurezza alimentare, la Cina ed il Mondo” tenutosi a Pechino il 1 luglio 2010. Pubblichiamo qui il testo integrale del discorso.

International Symposium

“Food Security: China and the World”

Beijing, 1st July, 2010

Speech of President Romano Prodi

The Challenge

We face three global crises. They concern environment, finance and food. The sharpest of them is the current financial collapse. The most frightening is the looming food crisis. The most alarming is the climate change. The three are different but closely interconnected.

This is not the place to go deeper into each of these challenges. Let me just recall that world population is growing by 220,000 people a day, and that there will be 3bn people living in 2050 with less than $2 a day. Urbanization means more demand for food to feed people, and for foodstuffs to feed livestock, with less farmers on the land to produce them. Production tends to move to the most competitive regions. Trade in food becomes more open, but ironically also more managed, because of concerns about food security.

An additional challenge is the increasing market volatility. Market volatility is the effect of stock fluctuations, food imbalances and market segmentation, exchange rates and consumer sensitivity to food quality, safety and price. There is also uncertainty regarding timing and application of innovations as regards biotechnology, nanotechnology, precision farming, carbon sequestration, and information technology. Finally, there is the challenge of who will pay for agricultural public services produced by land managers that the market does not pay for, such as rural landscape maintenance, environmental protection, and biodiversity.

Food Security

Farmland is under stress. For the World Earth Institute the main reasons of a tightening world food supply are population explosion, and accelerated urbanization, changes in life-stiles, falling water tables and diversion of irrigated water towards the cities. All this leads to losses in soil availability, quality and use for food. Water shortages translate into food shortages. While individuals drink only two to four liters of water (in different forms) a day, it takes 2,000 liters of water to produce the food an individual consumes daily (around one liter of water per calorie of food).

Other factors conspire to worsen the picture, such as continuing over plowing and overgrazing, increasing biomass production for fuel, a growing shift towards grain-based meat production in poorer countries, shrinking harvests with dwindling water resources and rising temperatures, and so forth. Farmers ask how they can balance food demand and supply, save energy and water, and preserve the environment, all at the same time. In any case I firmly think that the best use of diminishing water resources is not to produce more fuel and less food. We are indeed witnessing a mounting competition between food and fuel and a consequent structural shift in US and European agricultural markets.

Even if most of highly productive agricultural land is already exploited, there is still good potential new land for cultivation, notably in Latin America, Africa and east Europe. But, new land is insufficient. It is either inappropriate because of poor or polluted soils, or difficult to use for food production due to doubtful property rights and/or poor finance. Much potential food production on new land also suffers from government mismanagement, weak advisory extension services and lack of transportation infrastructure to reach the domestic and foreign markets.

To meet world demand the necessary food production growth will to a large extent have to be met by a rise in the productivity of the land already being farmed today. Technology can of course help to increase sustainable food production. Low- till or no-till farming techniques help retain water, raise soil carbon content, reduce energy needed for cultivation, as well as wind and water erosion, but up to a point. New technologies capable to raise land productivity are shrinking and will be of diminishing help as yields of wheat, rice, and corn press against the ceiling ultimately imposed by the limits of photosynthetic efficiency. Despite substantial expected yield increases in India, the USA, Russia and the Ukraine, it will therefore be extremely difficult to reverse the decline in the growth of global agricultural productivity from 4% p.a. in the sixties to eighties, to barely 1% in 2000 to 2030 (forecast).

Europe is currently the world’s largest food importer and also exporter. But its role as provider of food to the world is diminishing. The net crop-trade position of the EU-27 can be expected to deteriorate. Between 2003/05 and 2013/15 European Union demand for grains and oil seeds can be expected to increase more than its supplies. For wheat, the EU will move from a net exporter to a net importer position. Part of the explanation lies in a shift towards bio-fuel production. As a consequence the EU capacity to help fight world starvation will be reduced at a time in which food production will decline predominantly in those countries who already record increasing food import needs.

Europe is of course only one player but the same trend will characterize US agriculture. All countries will have to improve their food security policies. In many of them, in particular in Africa, one cannot expect to boost agricultural production without land reform and courageous food price policies helping the farmer and costly to the urbanite.

The food crunch may have eased, but make no mistake: the food crisis will come back. Developing countries spend about one third of the world’s food import bill and that bill is growing fast. FAO has warned against a “false sense of security” as it expects the current combination of low food prices, high input costs, and tightening export finance and conditions will unleash even more severe food crises than those experienced recently.

There are numerous signs of an international scramble for food, and beyond it a scramble for land to produce it. According to FAO, the race by some countries to secure farmland overseas risks creating a “neo-colonial system”. A growing number of countries, including China are seeking to lease or even buy vast areas of productive land, for instance in Madagascar, Ethiopia and the Sudan in order to satisfy their own domestic food demand. This scramble for land shows how important food security has become. One can well imagine what sort of political problems may eventually arise if a country hosting foreign investment in farming faced a serious food crisis.

Clearly, also banking crises have a substantial impact on food demand and supply, notably on planting, investments and trade. The world’s poorest developing countries lack the necessary credit lines to buy food; the great food exporters suffer from a lack of export finance. Food commodity markets are meanwhile so volatile and unpredictable, that barter trade has become too tempting to resist.

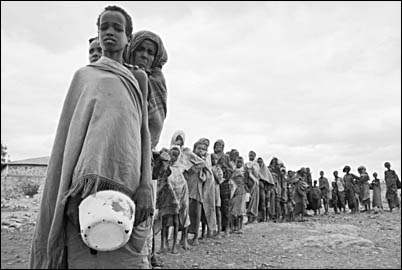

If there still is currently a reasonable balance between world food demand and food supply, this is only because there are about one billion hungry people and about another billion undernourished. If they had, as they should have, the income necessary to feed them, the world food picture would be catastrophic, with demand outstripping supply and prices shooting up. This would have very serious consequences for the food bills of the six dozen net-food-importing developing countries.

This overall negative prospect of world food imbalance cannot leave anybody indifferent, with nearly 3 billion people expected to be added to the world by 2050 (two thirds of whom in Asia and Africa) and 8 countries alone accounting then 4.7 billion people, most of whom have neither the climate, nor the soil or other conditions necessary to feed themselves in the future.

Environmental Security

Agriculture contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, can both suffer as well as benefit from changing climates.

In the long run, environmental security is the mirror image of food security, because there is no food without substantial clean water resources, productive soils, and appropriate climate. In turn, failure to tackle environmental degradation jeopardizes the future of agriculture and of the countryside. This notably calls for further reduction in the impact of agriculture on Greenhouse Gas emissions.

The search for more environmentally friendly agricultural inputs and practices must continue. Scientists are working to improve the efficiency of photosynthesis, carbon capture, nitrogen fixation and many other cellular processes that boost biomass yields. Biotechnology is expected to allow producing crops in soils lost to salinity, and use other marginal or unusable farmland. There are also prospects for heat-tolerant livestock breeds, and for modifications in animal diet patterns to reduce methane emissions. These are promising fields of research but it remains doubtful weather they can succeed to reverse the present trends of agricultural production.

Current agricultural policies need an overhaul in the light of the new challenges we face. They notably need to discourage unsustainable practices, and improve resource productivity (which becomes more important than labor productivity).

(According to the FAO, farming is responsible for 25% of CO2 emissions, largely from deforestation, 50% of methane emissions through rice and fermentation processes, and more than 75% of nitrous oxide emissions, mainly from fertilizer application.)

A new green revolution would not help to reduce emissions, limit soil deterioration or lessen water use, quite the opposite.

But we are not without instruments and means to find a way out of the corner in which we have pushed ourselves. For instance, the EU has succeeded in reducing the share of agriculture in EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 11% in 1990 to 9% in 2004.

At a time in which the trend in agricultural support is pointing downwards, whereas temperatures, emissions and environmental degradation are pointing upwards, growing attention is being devoted to the need to better meet public demand for public goods and services produced by farmers. Europe’s land managers help produce such public goods like eco-system services, including carbon sequestration and attractive landscapes. But European farmers still produce more “bads” than goods, that is, more pollution than a healthy environment. If nothing is done the environmental balance on our farms may worsen. If farm prices rise in the long term and presumably production costs as well, the opportunity cost for land managers of producing eco-systems and other public goods and services will rise as well. If direct farm payments are reduced after 2013, we might witness farming intensification and landscape neglect.

There are two ways out. Either one finds a method to attach an attractive price to these public resources, or – if one doesn’t know how, doesn’t want, or can’t do it -, one provides the subsidies necessary to ensure the production of the public goods that farmers can provide. In any event, in order to save our planet, we need to give a value to what cannot be bought such as many public goods.

International Trade in a Global Market

Globalization polarizes: some believe that it leads to the gates of salvation, that consumerism is the pass to happiness and that restraints of market excesses cause distress; others believe it is a “false dawn”, and a job killer, and that the winners of globalized financial systems are corporate raiders and speculators who capitalize on market volatility at the expense of productive workers and investors. This reflects the humus of today’s crisis of governance.

I don’t believe that the relentless pursuit of greed and acquisition in the global market system can lead to socially optimal outcomes. Nevertheless, I am a supporter of market globalization. Basically, because a working market is and will remain a motor of development, and because free trade based on competitive advantage is a plus for all participants.

In my view, we need to encourage profit seeking, but make sure at the same time that we give it a human face, and help cater for those that are less able to compete and are marginalized.

We need more responsibility and more fairness in world trade in order to avoid that globalization allow a few to enrich beyond belief excluding many others. This notably means special and differential treatment in favor of developing countries with temporary trade protection so as to allow them to catch up with the often more competitive advanced industrialized countries. The developing countries should notably be allowed to protect themselves from a food import surge. This was a major bone of contention in the Doha Round and actually caused its collapse without great hope for resumption any time soon.

The Doha Round cannot continue on the old track. OECD tariffs are particularly high for goods of relevance to poorer countries. One proof of this is that the US government collected more tariff revenue from the import of shoes (from less developed countries) than from the import of automobiles, even though the value of car imports was ten times higher than that of shoes.

As Nobel Prize Joseph Stiglitz wrote, if the Doha Round had been concluded as it nearly was, it would have penalized the developing countries, just as the Uruguay Round did. The reasons of this include “the loss of preference margins, the loss of revenue from trade taxes, institutional weaknesses, the absence of adequate safety nets, large implementation costs, lack of finance required to restructure the economy, and difficulties of the poor to manage short term employment. In most developing countries, supply constraints, low productivity, poor infrastructure, poor access to technology, imperfect markets make it impossible to take advantage of liberalized markets.”

Actually there is an important asymmetry of power in international negotiations: the developed countries gain in liberalizing their own markets, because they are able to adjust, and the disturbances posed to them by the developing countries are small. The developing countries are in a far more disadvantageous position; they can’t adjust unless they are given money and time. They may also have to accept exceedingly harsh conditions to accede to the WTO. As Stiglitz explained, “China had to agree to large tariff reductions in agriculture that went far beyond the obligations of existing members, and had to accept a special safeguard clause, in breach of the Most Favored Nation principle, allowing individual WTO members to take measures to limit imports of Chinese products in case of a surge. This could open the floodgate for the application of discriminatory measures against China.” Conversely, the US preferred to let the Doha Round fail rather than accept India’s request for an upsurge clause to protect its farmers.

To the extent that the world moves towards food scarcity, we could expect less competition among the producers of staple food for access to food markets, and more competition among net-food-importing countries for access to supplies. We could then see a different kind of trade protection with food import barriers giving way to export restrictions. Those countries producing bulk farm products that experienced periods of excess or high domestic demand, could then tend to refuse to meet import requests – as Vietnam did for instance denying China’s request for food in 2004 -, or impose export limits, or simply engage in barter trade.

Barter trade that imperils efficient resource allocation, siphons off food stocks to the detriment of other trading partners, and tends to limit competition and increase prices. This is not the scenario I prefer. And yet, there must be understanding for behavior dictated by real food security considerations, simply because no government can ignore them for its own safety. One could draw the conclusion from these several arguments that the Doha Round may have failed to focus on a new, different world in which food security considerations cannot simply be dealt with by liberalizing food trade.

Agriculture is the key to development and trade, because a majority of the people in developing countries lives from it. If one by magic stick removed all agricultural subsidies and import barriers, a few developing countries would benefit, but net-food-importing developing countries would suffer, because food prices would shoot up.

In any event, agriculture is different from any other sector – and ought to be considered so in trade negotiations – because of climate and geography, and because key factors of production such as land and labor are completely or largely immobile. Similarly, food is different from any other product category, because it is the foremost human need and right. This explains why every country in the world had adopted some sort of agricultural and even food policy, which it believes particularly suited to its needs. This may hinder some trade, but is not the ultimate factor hampering trade.

I believe the last trade round would have been concluded if there had not been more confident China and India as counterweight to the US and others. May be it was better so, and negotiations might resume one day if there can be agreement to achieve “Fair Trade for All”.

It is clear that we face a future of food scarcity, with high, albeit very volatile prices both for inputs and outputs. Food scarcity will be aggravated by managed trade and lack of finance, and eventually also by environmental degradation. Climate change puts all businesses and society at cumulative, long-term risk. The failure of agriculture alone would lead to widespread hunger in developing countries and mass migration of people (half a billion according to the UN).

The market has lost its magic. Recent events have proven that markets can fail. Failure can be tackled only via appropriate regulations. Open trade and related financing depend on it. Non-trade- distorting farm subsidies will have to stay, not just in Europe, but world wide, if food scarcity is not to worsen. However, we must also deal with our collective challenge to update existing national agricultural policies so that they maximize the capacity to meet domestic food demand, and, whenever possible, help satisfy a growing world demand. This requires agricultural policy reforms, notably in order to help mitigate, and adapt to climate change. Southern hemisphere countries will notably have to introduce land reforms allowing the poor to accede to the land, and adopt more appropriate food pricing policies. But this may not suffice. More ambitious environment policies will also be necessary so as to ensure the sustainability of increasing food production to feed the world, and contribute to adaptation to and mitigation of climate change.

The world’s farmers have a key role to play and have the right to ask how they can contribute to meet world food demand, save energy and water and conserve the environment. If we want to have enough food at affordable prices for everybody, we may also have to change our food habits, not to say our life-styles.

Conclusions

Drawing the conclusions, we are facing a difficult fundamental challenge: how to feed 9 billion people with the necessity of doubling the present food production from here to 2050.

It is a challenge that will be difficult to gain but dramatic to loose.

To avoid the tragedy we must act, considering that we don’t have time to wait.

In dealing with such a vital problem we must elaborate a line of action able to work even if something or everything goes wrong.

First: We must substantially increase the existing trend of agriculture productivity.

A world plan for enhancing Research and Development in agriculture is needed, creating the political, technical and economic conditions for a rapid worldwide diffusion of innovations.

National and international taskforces need to spread the knowledge of the best practices till the most neglected areas.

Second: We must put an end to the competition between energy and food.

Food must come first. A general constraint should be adopted to the incentives to non food agricultural productions.

Third: We need more land even if we must underline that the most productive land is already exploited and too much of it is used for urban purposes.

Fourth: We need better use of existing water.

A new policy for irrigation should be adopted implementing and diffusing the best water saving available technologies and run-off water from farms should be curtailed.

Therefore a deeper engagement concerning the use of the water of the big international river basins and an enhanced effort in developing salt-water-resistant harvests are indispensable.

This point connects the solution of food crisis to the energy production. The abundant supply of solar energy where China is now leader, will allow in 20 years large desalination of sea water. This way bring to agriculture large extension of today’s deserts.

Fifth: If we don’t implement these policies we will certainly face a general and unacceptable increase in food prices in a short period of time, with unbearable consequences of hunger and unrest.

I think therefore that, because of its growing role in world food and feed markets, China, should mobilize the US, the European Union, India, Brazil, Russia and other concerned countries, and table new proposals in order to face the dramatic food-security challenge.